The cathedral

Surrender, fragmentation, reformation

Hello. This post is about Death & Birds.

In the Summer of 2020, I spent an inordinate amount of time laying star-shaped in long grass. In hindsight, I think of it as research. When the world all but stopped, and we were mandated to stay at home, a hermitesque part of me knew exactly what to do: surrender. And surrender, I did.

My mornings consisted of taking the book ‘Devotions’ The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver, turning to a page at random, reading the first line and then closing the book to sit in contemplation of it. One day, that line was, “I don’t know who God is exactly”. “Me neither, Mary” I said aloud, before assuming my standard star-shaped position in the grass. I don’t know who God is exactly. Not a plane in the sky, not a car in the distance. Just trees, clouds, birdsong, and I don’t know who God is exactly.

The stillness of that time was almost eclipsed by the rabid uncertainty that accompanied it, but surrender was surrender, and the illusion of control had always been just that. I turned to lay on my side and was met by a greenfly, maybe three inches from my face. I watched as he made his way awkwardly, all elbows, up a blade of grass. Transfixed by the unfolding of his journey, I lost myself in him, until suddenly I was hit with a thought that made me gasp—oh! Oh it’s you! You, tiny, winged-alien, you are God!

The realisation rang through my body, and in that I moment I knew why I was alive. It was for this. It was to witness this greenfly walk this blade of grass.

Last week, we went to Winchester, and seeing as we were there, decided to visit the Cathedral. It is a spectacular building, parts of which date back a thousand years. Jane Austen is buried inside—on her gravestone, the “benevolence of her heart and sweetness of her temper” are mentioned, where her writing is not.

There are multiple books of Remembrance dotted around in glass cases; huge, open tomes listing all the names of the soldiers who died serving in various regiments during the World Wars. Fully allowing oneself to take in the colossal loss of life that those pages represent is totally overwhelming, and is perhaps the only appropriate way to respond.

A small, tucked away chapel that sits to the left of the vast building caught my eye. A sign outside suggests that it is a space for quiet contemplation, so before going in I lit two candles in memory of Norman and Simon, the pair of Sparrows who spent some time in my foster care, but who did not live to enjoy fully wild lives.

There is a special quality to the stillness in there, to anywhere thick with prayer, I suppose. It made easy surrendering to the seemingly bottomless well of gratitude and grief that I felt, that I feel, for having had the privilege of briefly coexisting with those two tiny, winged beings.

Outside the chapel I found David marvelling at more stained glass, and a male voice starts booming through multiple speakers, “Thank you for visiting Winchester Cathedral, please join us in our hourly recital of the Lords prayer”. Pointing at one of the speakers, David turns to me and mouths “Is that God?”. I nodded, solemnly, yes.

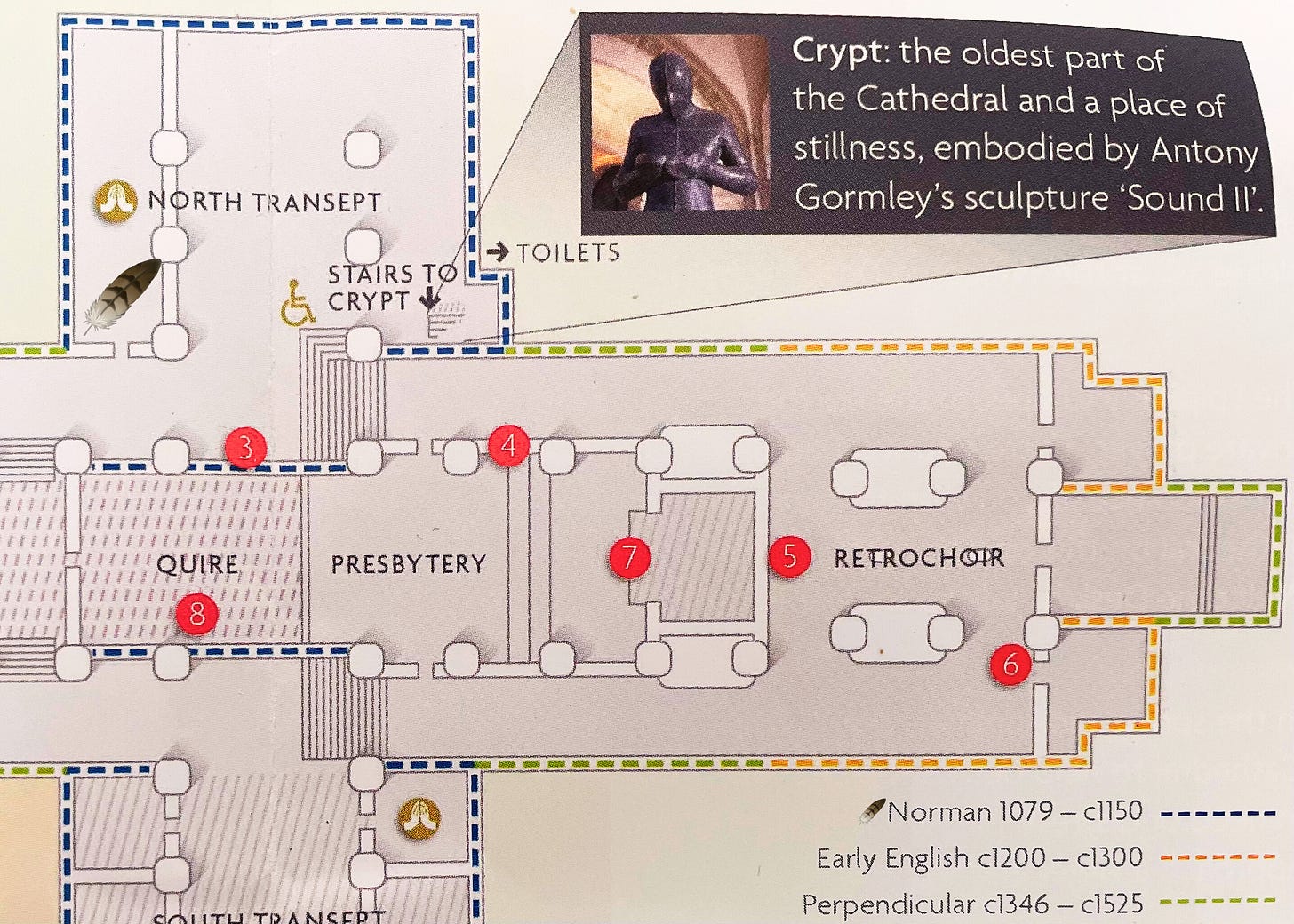

Afterwards, at lunch, I see on the Cathedral guide that the area which the chapel is housed within is, in fact, Norman. This makes me smile. I’ll take signs wherever I can get them.

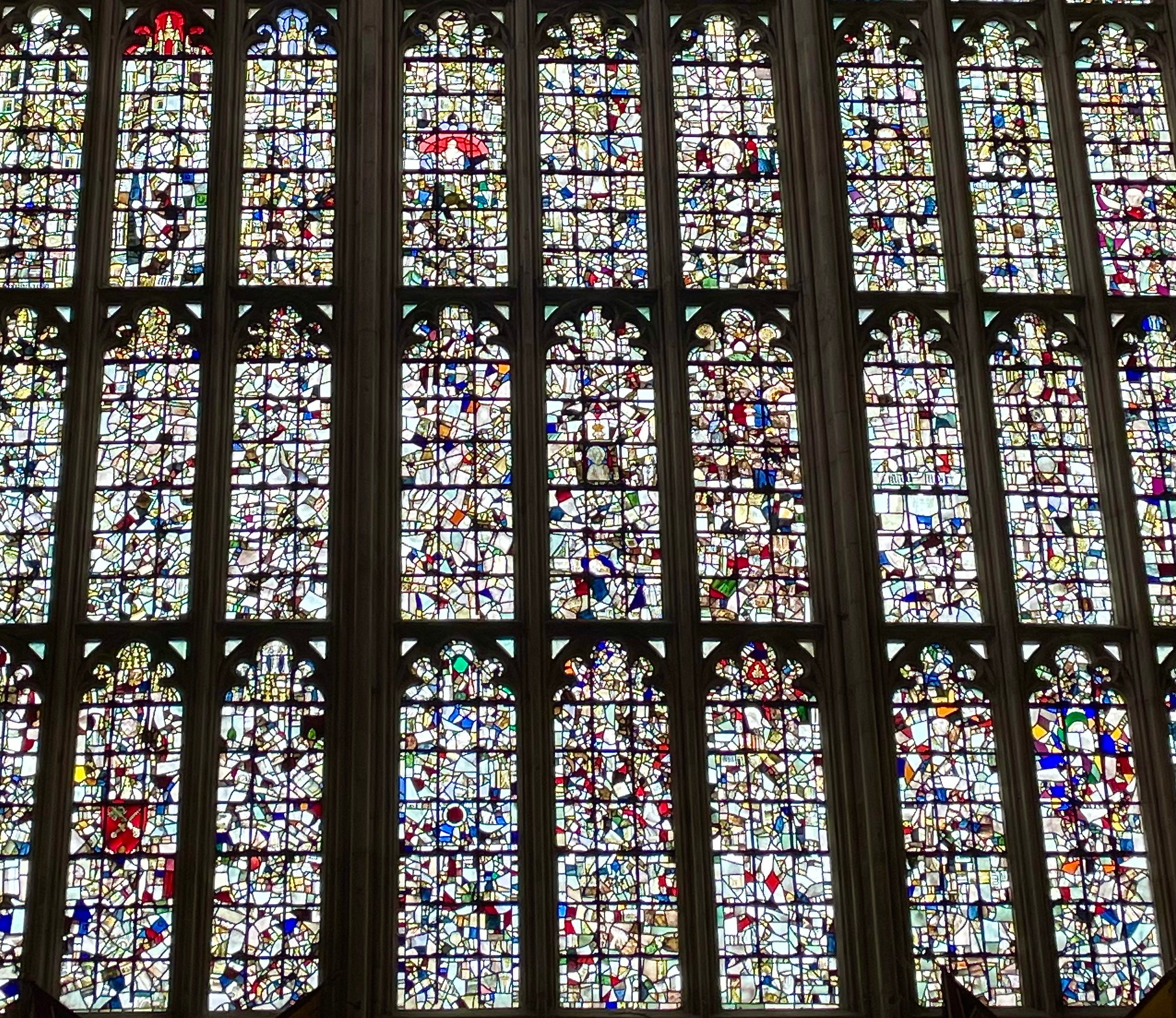

At the western facing end of the building sits the appropriately titled ‘Great West Window’, home to even more epic stained glass. In 1642, during the Civil War, Oliver Cromwell’s soldiers stormed the city and ransacked the Cathedral, opening mortuary chests and hurling the bones of kings and queens through the glass.

Local people salvaged the glass and the bones and kept them safe until 1660 when the monarchy was restored, and the window repaired. The broken glass was pieced together haphazardly to form the most beautiful, kaleidoscopic display of colour and history.

I love this window. I love how it speaks to fragility and impermanence—and to the potential beauty of fragmentation, and disorganised reformation.

I love to think of the many hands that gathered this glass, that kept it safe, and that painstakingly pieced it back together.

I love how they did not try to replicate the window to look as it did prior to its attack—that their rebuilding of this artwork acknowledges what it has suffered.

May we all be so kind.

Yours in aimless flight…

Your essays send me into little fits of joy. (And if you’re not already familiar with the Japanese art of Kintsugi, you will want to look it up—another culture’s recognition that to mend and repair, one mustn’t erase the broken bits. 💕

Beautiful, Chloe, as always. I am reading this from my office this week and even though I have a pile of things that must be done, I wanted to take a moment of stillness to read your post, because I knew it would have that calming effect of slowing things down and making me reflect. And it did, like your writing always does.

I knew not the history of those fragmented windows, so thank you. I also love the little sign from Norman.

Despite the unreality and uncertainty of those 2020 months, there was something to be said for just surrendering to being still and accepting the situation. It's become all too easy to be swept back up in routine now it's 2023. This was a good reminder to take moments and sit with them. The idea of doing that with a single line of poetry is wonderful.