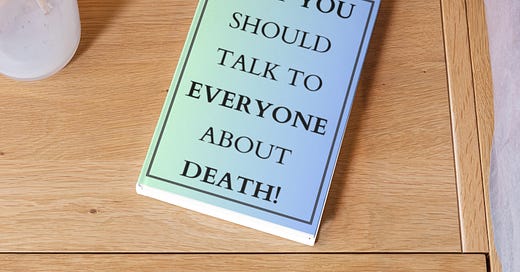

Hello. This post is about Death.

It feels important to begin by extending my deepest thanks to everyone who was so kind as to offer words of condolence, disbelief, and righteous anger in response to my last post. I’m still navigating my surprise at how generously people have been sharing in this space—a process that’s made me reassess a worldview that was perhaps, in hindsight, a little cynical. So, thank you.

Something that became crystal clear this last week, thanks again to the comments section, is that my chosen path is, at least in part, driven by a very young part of me wanting to correct something that happened decades ago. I shared in the comments (with the wildly talented David E. Perry) that my mother died in a state of denial. This was no ones fault, least of all hers. It is alarmingly common to deny Death, even when it is standing in the corner of the room; especially when the person dying is young.